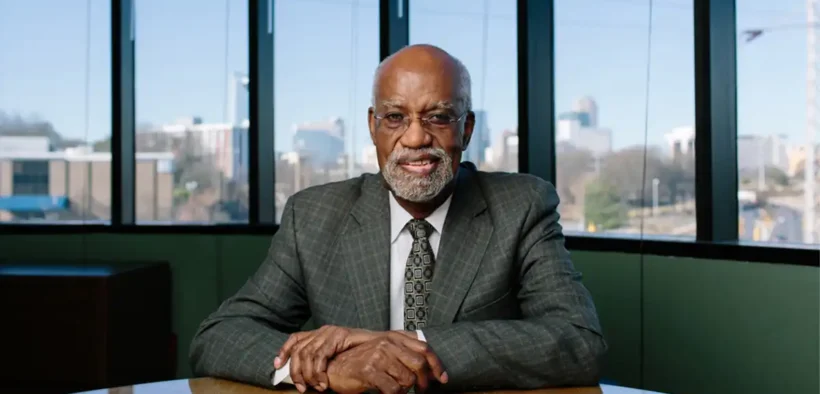

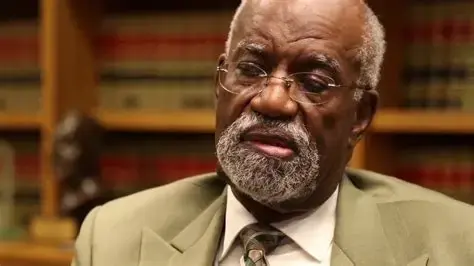

James E. Ferguson II, Civil Rights Attorney Who Fought School Segregation, Dies at 82

Share

James E. Ferguson II, a towering figure in the civil rights legal movement who spent more than five decades dismantling racial injustice in schools and courtrooms, died on July 21 in Charlotte, N.C. He was 82. His son, James Ferguson III, said the cause was complications of Covid-19 and pneumonia.

Early Activism in the Jim Crow South

Long before earning a law degree, Ferguson was deeply involved in the civil rights movement. As a young man in the segregated South, he organized classmates to challenge Jim Crow laws by integrating libraries, lunch counters, and other public spaces.

After graduating from Columbia Law School in 1967—where he was among fewer than 15 Black students in a class of 300—he co-founded Charlotte’s first racially integrated law firm alongside Julius Chambers and Adam Stein.

“We weren’t practicing law in the abstract,” Ferguson recalled in Race, Labor & Civil Rights (2008). “We were the legal arm of the civil rights movement in North Carolina.”

Landmark Court Battles

In 1971, Ferguson argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, helping secure a unanimous ruling that upheld busing as a constitutional means to integrate schools.

The case became a national blueprint for desegregation. During that fight, his law office was set on fire in an arson attack—an incident that underscored the risks civil rights lawyers faced.

Ferguson went on to play pivotal roles in overturning wrongful convictions. He fought for pardons for the Wilmington 10, a group of activists wrongly imprisoned for nearly a decade, and worked to reduce the sentences of the Charlotte Three.

In 2004, with the Innocence Project, he helped exonerate Darryl Hunt after 19 years behind bars, persuading an all-white jury with DNA evidence and new testimony.

“If you do justice to Darryl Hunt, you have done justice to the state, to the prosecution, to your country and yourselves,” he told jurors during the case.

Fighting the Death Penalty

Beginning in 2011, Ferguson used North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act to challenge death penalty sentences, successfully converting them to life imprisonment for four inmates. His work exposed systemic racial bias in capital punishment.

“He endured abuses and threats but made everyone feel seen and heard,” said attorney Sonya Pfeiffer, his longtime law partner. “What he did for schools across the country was extraordinary.”

A Global Civil Rights Advocate

Ferguson’s influence extended well beyond North Carolina. He trained Black lawyers during apartheid in South Africa, lectured at Harvard Law School, served as general counsel for the ACLU, and led the North Carolina Academy of Trial Lawyers.

In a 2016 interview with The Charlotte Post, Ferguson summed up his mission: “I just want to feel that I’ve done all I can do to bring about equality—for everybody. That’s what life is about—trying to create the society we think we want.”

Ferguson is survived by three children, a brother, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. His wife, Barbara, died in 2022.